DIS/MEMBER welcomes writers Sydney Bollinger and Grace Daly for a conversation about Daly‘s debut, The Scald-Crow (Creature Publishing, 2025). This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity and space.

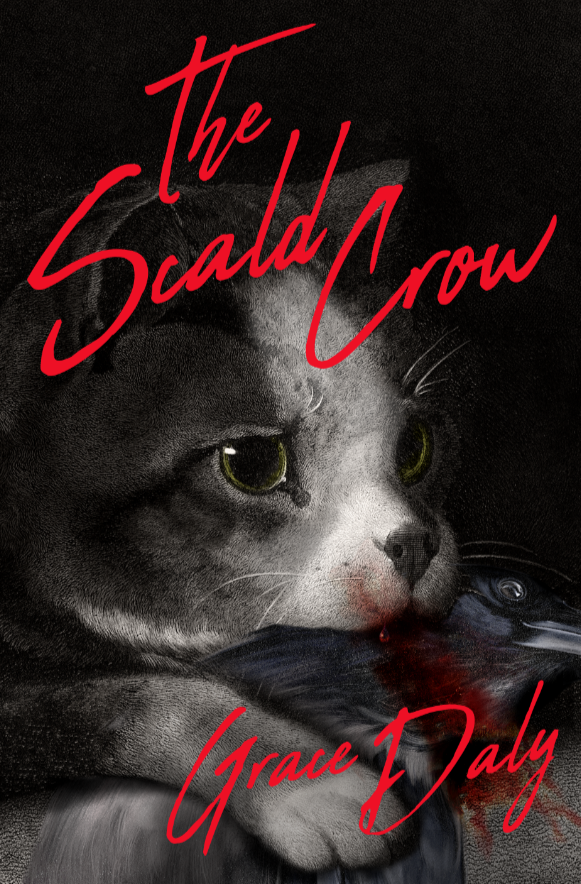

Grace Daly’s The Scald-Crow tells the story of Brigid, a young woman returning home after her mother goes missing. Between excruciating chronic pelvic pain, finding organs in all the wrong places, and a crow that won’t leave her alone, she must confront a dark past in her childhood home while just trying to survive. Daly’s book, which is on the 2025 Stoker Preliminary Ballot for Superior Achievement in a First Novel, shares the reality of living with an invisible illness in an oppressive world through Brigid’s voice and the physicality of her unknown condition. Without shying away from the blood and pain, we exist in Brigid’s world, and feel what she feels when dealing with both her haunted past and equally difficult present.

I found myself wincing when I felt Brigid’s pain, not only because it is similar to what I experience with my own invisible illness, but because Daly’s writing is unrelenting. Despite this, her incorporation of humor in Brigid’s narration lightens the load just enough to break through the darkness and come up for air. –Sydney

Sydney Bollinger: Can you tell me about the writing process for The Scald-Crow? When did you start writing and what led to it?

Grace Daly: I wrote it, primarily, in the second half of 2022 and started submitting it around. It was purchased in the summer of 2024 and came out in October 2025. The inspiration is multifaceted. Usually when I’m writing a full novel, it’s less that I have one idea for the novel and more like I take multiple different ideas for different stories and find a way to combine them. I have a notebook where I write down all of my ideas as they pop up, and I go through that notebook and find pieces I can combine into one cohesive story. Usually one idea doesn’t flesh out a full book for me.

One idea was based on a recurrent nightmare I had as a kid. It’s the nightmare in the book where the mother comes in and says, “I killed your mother. I put her in the closet and now I’m coming for you.” Separate from that, I had another idea for a book about a abuse dynamic where a demon from hell took the place of a real person who then became abusive, and then the abuse victim battles the demon to get the person back. That dovetailed nicely with the nightmare.

Also, I’m disabled. I have multiple chronic invisible illnesses and I wanted to write a book about somebody who had chronic invisible illness and suffered a lot of medical trauma and suffered from self-doubt. All three of these ideas melded together all at once, and I knew I wanted to write a book about how medical trauma and childhood relational trauma are kind of the same and how they feed into each other and the way that these systems can keep a person trapped. But I didn’t want it to be a huge bummer, so I turned it into a horror comedy, made it more punchy, and also dropped the demon angle and focused more on Irish folklore.

SB: What inspired the use of Irish folklore?

GD: I just love Irish folklore. I’m American Irish, and the only relative I had had who was really proud of their heritage was my grandmother, who was 100% Southside Chicago Irish. The house in The Scald-Crow is her house, down to the basket-weave shamrock painted teapot in the hutch.

SB: Can you talk more about how you characterize The Morrígan in The Scald-Crow?

GD: I formally apologize to Dr. Elizabeth Kempton Patterson, who is one of my good friends. She is a PhD and teaches at Lake County College in Illinois. She wrote her dissertation on the Morrígan and has a lot of very well-informed opinions about how the Morrígan was transformed from a very powerful and nuanced goddess into a kind of evil demon figure by the Catholic Church and anti-pagan ideology. She really doesn’t like it when the Morrígan is portrayed as some sort of evil twisted monster. She very kindly told me all about the Morrígan and taught me a lot about Morrígan folklore. And then I proceeded to make the Morrígan an evil twisted monster. I did incorporate some of her lessons about the Morrígan not being inherently evil and didn’t totally throw the Morrígan under the bus, but I mostly threw the Morrígan under the bus. I am sorry, Dr. Kempton Patterson.

I did add my own little twists. There’s no folklore I know of where the Morrígan tries to terrorize one individual, a child, or a specific woman in order to receive worship. The Morrígan is a big deal. She’s one of the major goddesses, so that wasn’t necessary. She’s partially based on real Irish folklore, but there is a little Grace Daly pizazz making her a separate thing in my universe versus classic folklore.

SB: The main character, Brigid, has extreme pelvic pain and has never received a diagnosis despite spending years seeking medical assistance, which we have both experienced. When we first chatted over email we mentioned us both having endometriosis and you also have adenomyosis. It takes forever to get a diagnosis.

GD: Forever! Which is so ridiculous because it’s so common.

SB: How does Brigid’s invisible illness relate to her understanding of herself?

GD: They are inextricably linked, and on multiple levels have messed with her self-concept. The medical trauma and the medical gaslighting have made her full of self-doubt. That’s a major theme a lot of disabled folks have connected with, especially invisibly disabled folks. There’s also these deeper pieces where she, and those of us who are disabled, really struggle with internalized ableism. She constantly feels like she’s not enough, she’s incapable, and she’s very broken. In the book, she very much wants to adopt a cat and keeps reminding herself that she’s not capable. Brigid says she can’t even take care of herself. Anytime anything bad happens, even if it’s clearly not her fault, she accepts the blame… It’s particularly heartbreaking because she is such a lovable, affable person. She’s funny. She’s caring. She’s gentle… Most of the readers can see it and the fact that Brigid can’t adds to the tragedy of her character.

SB: As a disabled author, what did you want to share about the experience of having an invisible illness through Brigid?

GD: I want people to connect their compassion for Brigid with compassion for themselves and compassion for other disabled people and victims of trauma. Someone messaged me recently, and said they are able-bodied and their disabled friend asked them to read The Scald-Crow to help understand the disabled friend’s perspective They said they feel a closeness with their friend that they didn’t have before and were able to have a great conversation.

I do hope not only are disabled, invisibly-ill people, and victims of trauma finding validation and compassion in this book, but I also hope that anybody able-bodied who reads it gets a more nuanced understanding of experience of living with an invisible disability and how challenging it is to face pain or obstacles that are just always there. I think it’s hard for people who haven’t experienced it to relate to, especially how it never stops. Even if you have a good day, it’s always in the back of your mind. You always have to manage it. There’s always the doctor’s appointments, the medications, the physical therapy schedule, the emotional therapy schedule… It’s an incredible extra load you have to carry, and you still have to do the laundry, clean the kitchen, buy your groceries, and make your dinner no matter how much pain you’re in. It’s important that able-bodied people get to see the unrelenting nature of it, because that’s difficult to imagine without having it.

SB: One of the most powerful moments in the book is when Dr. Hammerle says that Brigid has adenomyosis. This is the first doctor who actually confirmed there is something wrong and gives Brigid a clinical diagnosis. She tells Brigid there are ways to alleviate the symptoms. Brigid realizes the pain she’s been experiencing isn’t in her head and what she’s been telling herself isn’t true. Why is having the name so powerful? What gives that diagnosis power?

GD: My personal experience with the diagnosis of adenomyosis was very similar to Brigid’s. I distinctly remember my adenomyosis diagnosis as being particularly empowering because I found the symptoms of endo and adeno were so unpredictable, and the agony they caused added a layer of Hell. The diagnosis took away all of those labels like melodramatic, whiny, hypochondriac, and weak.

Instead of being told I just couldn’t hack it, I was told there was something fundamentally wrong with one of my organs. A switch flipped in my brain and my self-concept went from weak to strong. I wasn’t a whiny, anxious, weak woman who couldn’t handle the strain of modern life. I was a bright and talented woman who was doing her best while one of her internal organs was literally tearing itself apart for years. It was this incredible feeling of validation and relief to know there was no deep fundamental flaw about who I am as a person, and that the answer to my suffering wasn’t more suffering.

SB: I love that you weren’t afraid for things to be gross in the book and you really were able to get under my skin, especially in the scene of her trying to extract an organ from the garbage disposal and cleaning the rancid fridge. We also see the “grossness” of her body, especially in the scene where she wakes up and there is blood everywhere because of her condition.

GD: I wanted The Scald-Crow and the horror and the grossness to all feel very organic, and very much like meat. When I was younger, I used to think of myself and my body as two separate entities. There was the me who made decisions, had thoughts, and had a personality, and there was a suit I was piloting that was malfunctioning. Then I read an essay by Lisa Feldman Barrett about thinking of yourself and your body as two separate things. That’s erroneous because our brains evolved to serve the needs of our body, and our brain is an organ that’s also made of meat. There’s not a dichotomy between myself and my body. I am the meat. The meat is me. There’s no version of me where you scoop out my brain and put it in a jar and I still exist. It doesn’t work that way. A lot of the gore and body horror of the book comes from this concept. Brigid isn’t finding a heart in the garbage disposal. She’s finding her father’s heart. It’s not abstract. It’s not her dad’s body. It is her dad. When she is bleeding out, she is not passively experiencing it. It’s her.

SB: What did writing The Scald-Crow teach you about both writing and yourself?

GD: Before I wrote The Scald-Crow, I would write and spend a lot of time trying to come up with the most perfectly crafted sentences. I would care a lot about making sure I was using commas correctly and paying attention to how I was using alliteration and being purposeful with wordplay, and all that writer group stuff you’re taught to be mindful of. Sometimes it was very slow and sometimes it would feel like pulling teeth out of my skull.

When I wrote The Scald-Crow, since it was my first time writing a first person perspective, I just got right to it because instead of worrying about proving my value as a literary highbrow whatchamacallit. People are finding The Scald-Crow much easier to connect with than any of my highbrow art. I really view my writing as me trying to reach out to the reader and join palms with them. Writing like a person and being a person is so effective if your goal is connection.

Grace Daly (she/her) is a disabled author with multiple invisible chronic illnesses. She lives near Chicago and spends most of her free time with her dog, who is a very good boy. Her debut horror comedy novel, The Scald-Crow, is currently available and her fantasy novella, The Star of Kilnaely, is forthcoming in 2026. She has also been published in anthologies by Ghost Orchid Press and Sliced Up Press, as well as the podcast Tales to Terrify, among others. Visit her website or find her on Instagram and Bluesky for the latest news.

Sydney Bollinger (she/her) is a writer and editor. In 2020, she graduated with an MS in Environmental Studies with a focus on Environmental Writing from the University of Montana. Her creative work has been published in Northwest Review, Grimsy Literary Magazine, Hear Us Scream, This Present Former Glory, and other places. Her first zine, Death Wish, was published in 2023. Sydney regularly writes for the Arts & Entertainment beat in Charleston City Paper, and is a founding editor of Surge: The Lowcountry Climate Magazine and The Changing Times. Visit her website for more.

D/M thanks Sydney and Grace for this illuminating conversation. The Scald-Crow is available through Creature’s website and Bookshop. We wish it and Grace all the best in this year’s Stoker Awards. Happy reading, ghouls!