Guest columnist Edwin Callihan examines the cosmic legacy of Michael Mann’s 1986 adaptation Manhunter.

At this point, everybody knows Dr. Hannibal Lecter. Check the costumes at Spirit Halloween. His status as horror icon is firmly solidified in the horror pantheon of American Culture with Krueger, Vorhees, and Myers. Even if you haven’t seen The Silence of the Lambs (or the four other movies with Lecter) you’ve probably heard the often misquoted “Hello, Clarice” parodied too many times to laugh and too many times to care but that performance by Sir Anthony Hopkins landed him the Oscar for Best Actor in 1991. Yet, however menacing Hannibal the Cannibal may be, his criminal profile seems almost aristocratic compared to The Tooth Fairy, the primary antagonist of Michael Mann’s 1986 film Manhunter*.

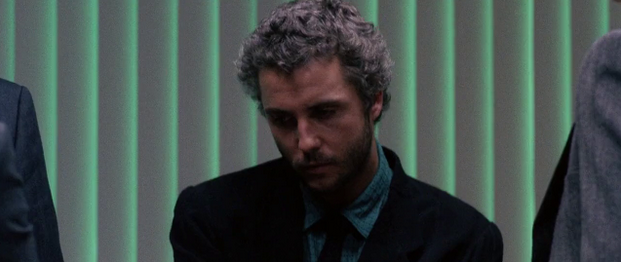

The Tooth Fairy fully embodies an uncompromising brutality only found in apex predators. Maybe that’s what keeps him from being a Funko Pop. He definitely doesn’t have the sex appeal of Dr. Lector. So who the heck is the Tooth Fairy anyway? The Tooth Fairy is a serial killer who murders by the full moon, slaying entire families—wife, kids, dog, whatever. The alias comes from the bite marks left on the female victims. The Tooth Fairy’s real name is Francis Dollarhyde, a lonely film technician with a traumatic childhood and a scar from corrective surgery to fix his facial disfiguration. He is a looming, large and intimidating man with low self-esteem and tremendous strength. He hides his speech impediment, avoids most social interactions, and is feared among his co-workers for his size and awkwardness. Dollarhyde justifies his killings as a transformative process—a ritual—each murder leading him closer to his final form: The Red Dragon, which comes from his obsession with the painting “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun” by Romantic artist William Blake.

The Red Dragon was all he had for a long time. It was not all he had now. He felt the beginning of an erection.

In Manhunter, The Tooth Fairy is pursued by traumatized FBI profiler Will Graham (portrayed by William Petersen), whose ability to empathize with criminality enables his successful apprehension of psychopaths including Dr. Hannibal Leckter (played in this film by Brian Cox and spelled with a “ck”, long before Hopkins took on the role). Throughout the film, Graham obsessively pores over the disturbing crime scene photographs and rewatches the murdered families’ private home videos–mirroring, unbeknownst to him, the meticulous methods of The Tooth Fairy.

Mann establishes early on Graham’s almost-telepathic connection to Dollarhyde, while Graham constantly struggles with this intuitive process. He is consistently framed in geometric shapes of modern architecture, such as the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia. This reflects his devotion to the methodology of psychological profiling. These shapes and lines intersect in perfect contrast with signature noir chiaroscuro and, at times, internal monologues walking us through the crimes. Graham is a prisoner of his own ethical trappings, forced to rationalize violence and inhumanity in a “civilized” society.

In the novel, Dollarhyde’s interactions with his alter-ego are occult-esque and, from his perspective, bend physical limitations of the material world. To wit: “The picture stunned him the first time he saw it. Never before had he seen anything that approached his graphic thought. He felt that Blake must have peeked in his ears, might be visible in the darkroom, might fog the film. He put cotton balls in his ears. Then, fearing that cotton was too flammable, pieces of asbestos cloth from an ironing-board cover and rolled them into little pills that would fit in his ears.”

Yet Harris, with masterful restraint, is able to keep the narrative firmly grounded in realism. Rather than emphasizing a cheap supernatural element at play, he utilizes the transcendental effect of art and its ability to stimulate religious ecstasy with maximum impact. This functions as a core tenet of what I consider “Cosmic Realism.”

Cosmic Realism rejects the supernatural and diverts the speculative as a plot device, embracing empiricism while also recognizing the sublime and natural forces that exist within nature are indifferent and incomprehensible to the human psyche, threatening to our existence no matter what beauty may be found in our rationalizations. The novel has more room to explore the characters’ psychology. In the following passage, The Red Dragon begins to “speak” in an entirely distinct voice. Most readers assume this is a symptom of psychosis, but are nonetheless suspicious of unseen forces. His blind love interest, Reba, is seemingly unable to distinguish Francis’ voice in a phone call:

“TELL HER TO COME OVER TONIGHT AND TAKE CARE OF YOU.”

Dolarhyde** almost got his hand over the mouthpiece in time. “My God, what was that? Is somebody with you?”

“The radio, I grabbed the wrong knob.”

It checks all the boxes for a cosmic horror story, doesn’t it? There is even a “cursed” book in which Francis stores some hidden knowledge that invokes flashbacks of his disfigurement, his abusive grandmother, and a dilapidated old mansion estate. Additionally, Francis believes he summons a powerful entity through ritual murder based upon the cycle of the full moon… Not far off from the likes of something out of an issue of Weird Tales, huh? Yet there is nothing supernatural at play. Nothing. The novel itself owes a great debt to Robert Bloch’s Psycho, arguably the blueprint for the postmodern horror film. Bloch was a disciple of H.P. Lovecraft, and penned several cosmic horror tales before jumping genres exclusively into crime thrillers. Hitchcock’s iconic film omits the more revealing nature of Norman Bates’ previous occult interests, however this passage from the novel shows us a little more for intrigue:

Here Lila found herself pausing, puzzling, then peering in perplexity at the incongruous contents of Norman Bates’s Library. A New Model of the Universe, The Extension of Consciousness. The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, Dimension and Being. These were not the books of a small boy, and they were equally out of place in the home of a rural motel proprietor. She scanned the shelves rapidly. Abnormal psychology, occultism, theosophy.

Bloch had not forgotten his roots but he also didn’t explicitly direct us to the “unreal.” But like Hitchcock, Mann also chops much of the character development and backstory established by Harris in favor of a sleek, dreamy audio-visual presentation that adds to the ethereal quality of the narrative. While the film remains faithful to the source material for most of the runtime, there are several exorcised scenes and drastic changes in the ending, allowing the film to breathe without obfuscation.

Manhunter is ritual-like and coded with many elaborate cues, operating more as a visual collage. We see an unconditional dedication to style and moody atmospheres that dissect human nature and our own personal relationship with violence. The style is accented by intense, specific color tints derived from Blake’s “Red Dragon” painting. These colors act as spiritual auras, emanating the characters’ emotional reverb within the narrative.

Graham’s home is always bathed in rich blue for peace, tranquility, and detachment from his FBI work. Red and yellow palettes (The Red Dragon, The Sun) forces us to confront violence and sexuality’s interconnectedness. Wide angles stage the intensity of drama, thrusting us into the illusion that we are present in the scene ourselves. The film also hyper-focuses on the forensic profiling process, accurately represented through scenes with Graham, Jack Crawford, and FBI associates which reinforces authenticity and commitment to realism. Mann’s incorporation of popular music also radically welcomes us into the narrative, humanizing the disturbing matters in a relevant new-wave fashion. Lots of neon lights, lots of art deco, and fashionable garments (Tooth Fairy rocks a designer silk button ups and some fly retro shades) allow us to descend hand-in-hand with pop culture and violence.

Francis Dollarhyde, masterfully portrayed by Tom Noonan, creates a most dramatic character study. One scene particularly shows his virtuoso skills as he towers over the sleazy reporter, Freddy Lounds (Stephen Lang), with a pair of stockings pulled over his face. As he shows Lounds images of his gruesome crimes, he says: You are an ant in the afterbirth. The statement leans to a deeply unsettling cosmic manifesto. Behind Francis is a television scrambling with white noise and a giant backdrop of a non-terrestrial surface in the vastness of outer space.

This image asserts that his capacity for violence is indifferent to pleas for mercy, to prayers, to our suffering. Dollarhyde desires to be beyond good and evil, far from earthly moral convictions, and be engulfed into the mysteries of cosmic depths… to be the Red Dragon. Dollarhyde is intelligent, meticulous, and an enigma to Will Graham, operating on a powerful wavelength akin to a brooding storm. Yes, very much so a real force of nature.

Manhunter inverts the empiricism of behavioral profiling by confronting the incomprehensible awe of human violence. We are given a brief glimpse into the POV of Dollarhyde, sometimes through the meditations of Will Graham himself, bridging the gray area between Good and Bad and challenging their distinction. Between Will Graham and Dollarhyde, Cox‘s Dr. Leckter exists as a manipulative shaman guiding them through a dim corner of these unknowns, the only one to seemingly belong to the gray area of man and monster.

Dollarhyde smashes the mirrors in his victims’ homes, unable to look at himself due to immense shame from his crimes, yet he is still compelled to kill and when he does, he sees a glowing light shine from the victims eyes in an almost-cosmic way. Our moral compass is challenged as voyeurs in our complicity to spectate true horror, not fantasy. This also shows us that this murderer is not some evil summoned from another dimension or an alien invader from the stars, no, in fact he is very human. Society views Dollarhyde as a monster, but Will Graham understands that even if he is a “monster,” he is man with emotions, with a past, and most importantly, made up of the same flesh and blood as each of us.

The audience wrestles with the very human qualities of Francis Dollarhyde, Tooth Fairy. We watch him fall in love with his coworker, Reba, who reciprocates his intimacy, leading to further challenges with his self-esteem. In the climactic finish, moved by the song “In A Gadda Da Vida” by Iron Butterfly, Dollarhyde is completely consumed by The Red Dragon and he takes several gun shots to his body, never even flinching as he barrels toward Will Graham. Is he just a man or a juggernaut of cosmic brute force? Is he the uncompromising storm? Is he really the Red Dragon? A single bullet to the head may be the only answer.

Why do people do bad things? Blame drugs, communism, movies, music, sex, Satan. Options are endless. Pick one. Dollarhyde’s catalyst was a powerful William Blake painting. Will Graham and perhaps even Dr. Lecter might argue that it was repressed trauma, a deep hatred for his granny, but not everybody with a bad childhood becomes a murderer. So what is it? What drives a person to such violence?

Today, crime is sexy and in a world where people are calling Jeffrey Dahmer “hot,” it’s fair to say the modern social constitution of Western society affords us gratuitous liberty to freely express our voyeuristic desire and obsession with homicide. But violence? Violence is in our nature. Violence is nature. Let’s be real: it is deeply rooted in our instincts of survival according to Charles Darwin. What about the dramatic creation of the cosmos itself? Certainly The Big Bang can be considered a “Violent Act,” a God-like explosion that seeded stardust across an empty void and collided long enough to shit out galaxies, solar systems, and finally little old Earth. I think so. And here we are—hi—after a few millennia, we’re still committing violence under the tyranny of nature. Always paranoid of the lurking fear of terrestrial disasters, nuclear holocaust, asteroids, gamma ray bursts, solar flares…

The whole Universe ain’t safe.

Edwin Callihan is the author of Strange Spells, Histories of Mgo, and assorted weird tales. Find his work at Castaigne Publishing and Filthy Loot.

Edwin Callihan is the author of Strange Spells, Histories of Mgo, and assorted weird tales. Find his work at Castaigne Publishing and Filthy Loot.

*Manhunter is the first onscreen adaptation of Thomas Harris’s 1981 debut novel, Red Dragon. Ignore Brett Ratner’s 2002 version with Ed Norton. Shit suckkkkkssss.

**’Dolarhyde’ is the spelling used in the novel.