Frankenstein

Starring: Oscar Isaac, Mia Goth, Jacob Elordi, and Christoph Waltz

Adapted & Directed by: Guillermo del Toro

Goths, rejoice! Two titans of supernatural sentiment, Guillermo del Toro and Mary Shelley, have joined forces in our hour of need to deliver a meditation on life, death, and the uncanny power in between. Frankenstein arrived in limited theater release this past week, opening the book into Halloween just as October’s final leaves begin to fall. The master filmmaker’s newest foray into adaptations feels–from its all-star lineup of Oscar Isaac, Christoph Waltz, and Mia Goth to its monolithic sets and 2.5-hour runtime–too big to fail. Yet it’s relative newcomer Jacob Elordi, following in Nosferatu and Bill Skarsgaard‘s footsteps of “hot guy playing monster,” who really brings the movie to unnatural life.

It’s unsurprising to hear that Frankenstein is, per del Toro, “[my] favorite novel in the world.” Shelley‘s masterpiece created the template not just for science fiction and horror broadly, but for body and technological horror specifically. If H.R. Giger‘s Alien designs made the erotic body horrifying, and if David Cronenberg‘s films eroticize the abject body, then del Toro‘s oeuvre plays in their middle ground, exploring the erotics of fabrication. He’s known for creature features and masterful puppetry, winning Academy Awards for Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water, and Pinocchio, three films with mesmerizing practical effects. He’s partially responsible for major crush objects Hellboy and The Amphibian Man, gamely catering to the monsterfucker demographic.

And 2015’s Crimson Peak, a somewhat overlooked dark romance, also sees its ship come in with Frankenstein. The films share soaring backdrops studded with textural goodies, blazing red motifs, sumptuous costuming, murky and troubling relationships. When the eponymous Victor Frankenstein is driven from academia, he retreats not to an ivory tower but a decaying one reminiscent of Crimson Peak’s manor, retrofitting its insides with the latest in medical and electrical gear. Gothic fiction, emerging as it did alongside experiments in scientific development, has always commented on technology. The past’s inexorable grasp on the present, Gothic’s main concern, drives Frankenstein as well as coming home to roost in our era. The solitary technologist, an arrogant Ideas Man convinced reality can bend to his will, is a villain for our times.

Oscar Isaac has played a tech villain before. Sharp-eyed viewers might read Frankenstein in conversation with Ex Machina, a “Bluebeard’s Chamber” fairy tale and thus in debt to the Gothic tradition, as is the more obvious and straightforward Shelley adaptation. Yet there’s more to this relationship than just a one-to-one meeting of the megaminds, or even their beverage tells (green smoothies for Ex Machina‘s Nathan, milk for Victor. True villain shit).

Nathan and Victor share a poisonous worldview lousy with stolen valor, exemplified visually by the Medusa carving in Victor’s workspace and the soldiers’ bodies he scavenges for his experiments. They live in remote structures whose functions collapse the boundaries between work and self, simultaneously advanced and atavistic. They’re willing to play God… and unwilling to engage with the logical end-points of their experimentation. Though both do get their hands dirty by building and rebuilding humans and machines, their positioning with regard to their creations is peculiar. They require intermediaries to test the success of their creations. They are unwilling to become emotionally involved.

Mia Goth‘s Elizabeth, on the other hand, is emotionally involved the moment she meets the Creature. Depicted in the 2025 film not as Victor’s fiancee but the intended of his doomed brother, she’s also fresh from a convent and a bug enthusiast. She challenges Victor at every turn, and although she spurns his sexual attention, her greatest betrayal–in his eyes–comes in her attitude toward the Creature. Curious where even Victor is revolted, gentle where he replicates his own father’s abuses: it’s no surprise that the Creature’s second spoken word is “Elizabeth.” In his first word lies Frankenstein‘s conundrum and its power. On first meeting, Victor names himself to his creation, but doesn’t name the Creature. Victor, the Creature repeats, and draws his hand toward his own chest. In this void of understanding, Victor is the world for self. It means man; it means me.

Gothic literature is stuffed with doubles, doppelgangers, foils, and mirrors. Notably, Goth plays not only Victor’s would-be lover but his mother. The crucial twinning of Victor and the Creature has prompted one of Frankenstein‘s major legacies: the popular confusion over which character is the monster. A second foil for Victor appears in Herr Harlander, Elizabeth’s uncle. Played with louche cunning by Christoph Waltz, Hollander is a former Army surgeon and arms dealer, a Faustian Godfather in gold-soled boots who offers Victor all the bankroll he requires… for the small price of a future favor, of course.

When that favor is called in, it’s beyond even what Victor is willing to do. Waltz handily steals every scene he’s in, his character providing sly flirtations, the most gallows of humor, and bleak commentary on what happens when warfare bankrolls science. He lacks even the scruples Victor pretends to, those of high-minded scientific endeavor and bold experimentation. But he and Victor share an essential contempt for life, despite their deep cognizance of its processes. The determination to overcome death is really a lack of respect for life and its ugly, gross, fatal realities. Ironic, for dealers in death and harvesters of bodies, but not unfamiliar.

Ultimately, Frankenstein invites the audience into life. Its settings, costumes, and props are textbook del Toro (when they aren’t obviously Netflix): monumental and yet accessible, inviting and yet ominous, the most grotesque imagery made beautiful by loving attention to detail. It’s undeniably in the grand Gothic-revival lineage of Bram Stoker‘s Dracula, elements such as Baroness Frankenstein’s tomb and Elizabeth’s wedding dress calling to Eiko Ishioka‘s famous costuming and design.

The aforementioned red motif flows through the film like an opened vein, inviting instinctive comparison between gored flesh and crimson silk. The color red ties Victor to his deceased, perhaps too beloved mother–and to the Creature. Her scarlet scarf is Victor’s constant accessory, its narrow width expanding to become a wrap barely covering him when the Creature enters his bedroom. It’s a scene shot as the meeting of two lovers, rather than father and child. Victor’s framing, and the Creature’s, call to depictions of nightmares and demon lovers. There’s a confusion of feeling in this turning-point, as there is when Victor meets Elizabeth for the first time and falters, whether because she is so beautiful or because she reminds him of his mother. Both are indicative of del Toro‘s willingness to gesture toward the Gothic’s complicated, hidden, and even incestuous relationships.

The success of a multifaceted creator-Creature relationship is due in no small part to Jacob Elordi. With a resume tending toward more mainstream fare, Frankenstein‘s success should pave the way for Elordi‘s turn as another Gothic antihero, Heathcliff in 2026’s Wuthering Heights. Earlier attempts at Frankenstein had del Toro staple and fan-favorite Doug Jones as the Creature. Then Beloved of Girl Internet Andrew Garfield was slated for the part.

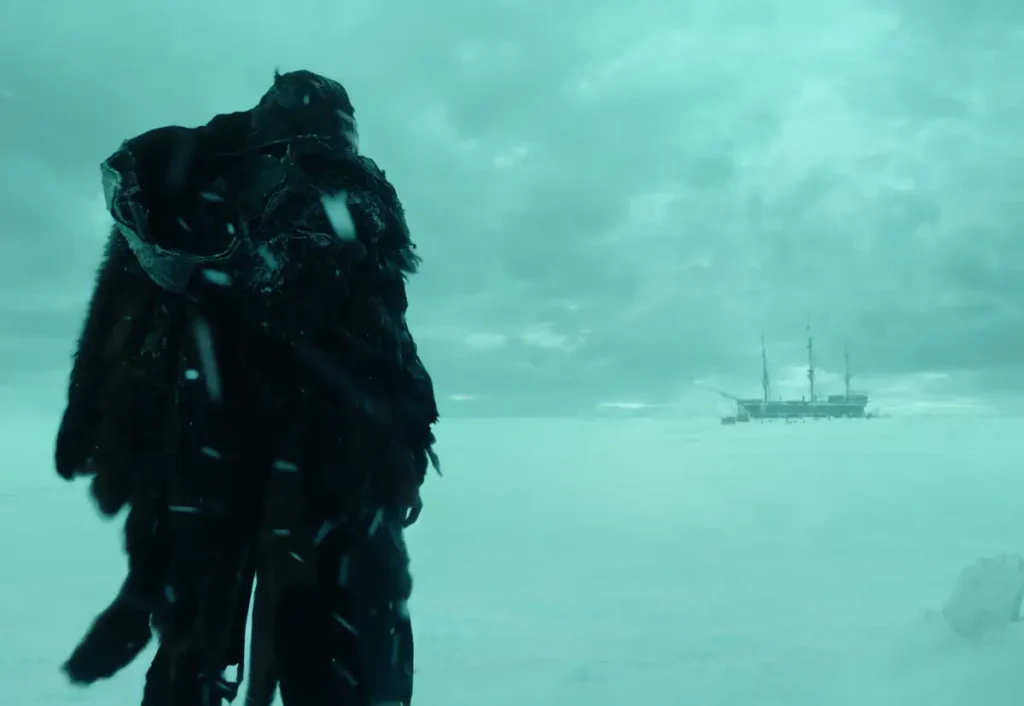

Despite being conventionally hot, Elordi carries the role off with pathos and true menace. When hot guys play monster, it helps to be tall (Elordi is 6’5, Boris Karloff as the OG Creature 6’6 in his boots); the Creature’s costuming and shot framing add to his elongated, imposing alienness. Whether wearing only bandages or swathed in black tatters, the Creature is otherworldly, oddly ethereal for a being we’ve witnessed be constructed through brutality. There’s impressive physical acting at work, given that the first chunk of the Creature’s screentime is punctuated only by others’ voices. Elordi‘s silence, halting speech, and finally brief but cutting dialogue provides perfect contrast to Isaac‘s bombast and self-consciousness.

This tug-of-war between what’s said and what’s shown, appearances and true natures, what’s thrust upon us and what’s within our control, is the core of the creator-Creature relationship. When the Creature tells his tale, it’s one of transformation.

One reason Mary Shelley‘s novel has withstood the test of time is its fluidity. For every reader and every era, there’s an interpretation. In 2025, Frankenstein feels more urgent than ever. Its director has spoken bluntly about so-called generative AI, a position and topic that refract Frankenstein‘s concerns in provocative ways. The book’s themes, at once timely and perennial, remind us that the past is not even past, that the future doesn’t just happen, but is constructed–and asks us to consider who is doing the constructing. Del Toro‘s Frankenstein embraces the tension between hero and villain, parent and child, creator and creation, and offers an audacious portrait of the ways we create ourselves.